This is the third and longest part of a paper that I presented at the recent Latin American Studies Association (LASA) conference in Lima. (The first part of the paper, called called ‘Introduction: Origins, Globalization and Uses of Ayahuasca’ can be read here and the second part can be read here.)

i) Post-colonial Perspectives.

The remainder of this paper will take the Peruvian cultural anthropologist, Marisol De La Cadena’s, book (2015) ‘Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds’ as a point of departure to continue to examine the kinds of sense-making discourses that are available to understand the experience of drinking ayahuasca.

This will be done in two ways. First, in more general, theoretical terms, by looking at how plant spirits, following on from De La Cadena’s work on earth-beings, can be made sense of and entered into relationship with: and, secondly, in a more personal and direct way, using terms from her book, reflecting on the difficulties in translation, the necessary equivocations and the partial connectivity between my world and the world of my Shipibo teacher.

Before beginning this, I want to situate the work of De La Cadena, as she herself does, in the legacy of post-colonial studies. She acknowledges a huge debt to the many anthropologists and other thinkers who have worked hard to free anthropology and related disciplines of its colonialist beginnings and assumptions.

Comaroff J. & J., say (1991:15) that:

“The essence of colonization inheres less in political overrule than in seizing and transforming “others” by the very act of conceptualizing, inscribing, and interacting with them on terms not of their choosing….……… in assuming the capacity to “represent” them, the active verb itself conflating politics and poetics.”

One of the many remarkable features of De La Cadena’s book is her rigorous insistence on understanding the experiences of her two key collaborators, Mariano and Nazario Turpo, in their own terms, whilst still deploying the full range of Western academic resources available to her, as well as the shared cultural frames of references she has with her collaborators for being Peruvian, albeit from very different geographical and sociocultural worlds in Peru. She is constantly alive to the difficulties in understanding the stories of the events they tell her, and the written archive she has access to, in the terms of the speakers rather than her own terms, and to the interplay between her ideas and the stories of her collaborators and to the ways in which ethnographical practices and discourses from her academic discipline can invalidate important aspects of their life-worlds.

She uses the work of the Brazilian anthropologist, Viveiros de Castro (2004b) to speak of ‘controlled equivocations’ – the inevitable difficulty in translating between very different worlds, even when they appear to have terms in common. Following Viveiros, she says the best that can be done in this situation is to be aware of these equivocations as points of difference and resist the temptation to eliminate them. Later in this paper, I will return to this idea of ‘equivocation’ as I have experienced it with my Shipibo teacher.

ii) Nature and Culture.

“In the oldest religion, everything was alive, not supernaturally but naturally alive. There were only deeper and deeper streams of life, vibrations of life more and more vast. So rocks were alive, but a mountain had a deeper, vaster life than a rock, and it was much harder for man to bring his spirit, or his energy, into contact with the life of the mountain, and so he drew strength from the mountain, as from a great standing well of life, than it was to come into contact with the rock.” D.H. Lawrence, “New Mexico” (2014)

One of the key unquestioned assumptions, which De La Cadena still observes in the work of many postcolonial thinkers, concerns the relationship between nature and culture. De La Cadena, in common with other contemporary anthropologists (Vivieros de Castro, 1998; Descale. 2013; Kohn, 2013; Escobar 2014) wants to re-think the centuries-long dualism between nature and culture. In particular, this means that agency and ontology are seen as fundamental characteristics of the non-human world. Such a move challenges and goes beyond the founding assumptions of the whole Enlightenment project of modernity.

Latour’s work (1993) is highly significant for De La Cadena in showing the importance this ontological distinction between nature and culture has played in the roots of modernity and European expansionism, and how this distinction has been incorporated into the modern political state.

De La Cadena sees Latour as building on the work of historians of science Shapin and Schaffer (1985) on the philosophical and methodological dispute in the 1660’s between Robert Boyle and Thomas Hobbes over Robert Boyle’s air-pump experiments. She quotes Latour as saying that they were “like a pair of Founding Fathers, acting in concert to promote one and the same innovation in political theory: the representation of nonhumans belongs to politics, but politics is not allowed to have any relation to the nonhumans produced and mobilized by science and technology.” (Latour, 1993, 28)

She goes on to say that (De La Cadena, 2015, p. 92): “This, Latour proposed, inaugurated what he called the “modern constitution”: the invention of the ontological distinction between humans and nonhumans, and the practices that allowed for both their mixture and separation. Enabled by (and enabling) the European expansion, the modern constitution was at the heart of the invention of both modern experimental science (and its objects) and the coloniality of modern politics.”

As already noted, the ontological distinction between humans and nonhumans is a central thread of this paper. My earlier argument, to recap it here, is that the five common discourses used by Westerners to make sense of their ayahausca experiences tend to reinforce the traditional dividing line between nature and culture and subject and object, even when the nature of these experiences point beyond these dualisms.

Drinking ayahuasca provides many people with powerfully felt, noetic experiences of the lived realities of nonhuman realms, which have their own ontology and agency – animal and plant spirits, earth beings, angelic and diabolic beings, malevolent entities, spirits of places, the spirits of our ancestors, even other-dimensional worlds of aliens or other strange beings. Drinking ayahuasca indicates that these worlds do not exist in a separate realm apart from what is understood to be everyday, consensus reality but interpenetrate with and effect it. It is this connection between the worlds that both makes healing and witchcraft – in the sense of the capacity to do harm to people – possible.

The great achievement of De La Cadena’s book is to take seriously the nonhuman beings she refers to as earth-beings, that are central to the way of Andean life she is exploring through her research, and accept they can play a role in human affairs and politics, as her two principal collaborators insist. I now want to turn to the way that De La Cadena writes about these earth–beings and relate it to my own experiences of plant spirits, encountered through the intermediary of La Madre Ayahuasca.

iii) Earth-Beings and Plant Spirits.

When I first read ‘Earth-Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds’ just over six months ago in September 2016, I was struck by two things. The first was the resonance between some of the themes of the book, especially her relationship to her two principal collaborators, and the forms of practice they engaged in with earth-beings, and my own experience over five years working with my Shipibo Maestro (teacher) drinking ayahuasca and dieting different palos (plants and trees). In particular, I found the idea of the necessary equivocation between radically different life worlds useful to understand aspects of my relationship with my Maestro. This will be the theme of the next section of this paper.

The second area that had a great impact on me was the meticulous way that De La Cadena wrote about earth-beings, crediting them with an existence and agency usually denied to them by non-indigenous people and researchers, who typically categorize them as religious or spiriritual or cultural beliefs. At its colonialist worst, describing them as beliefs can be portrayed as evidence of the superstitious and pre-modern ways of thinking of indigenous people that they need to be rescued from by a modern education.

At its post-modern best, referring to the practices related to earth beings as beliefs can be seen as examples of different cultural worldviews in a multicultural world, in which no one belief has a privileged position. It is to De La Cadena’s great credit that she refuses to subsume earth beings under the notion of beliefs.

At the same time, though, on first reading, I was disappointed to find no personal account of her experiences with earth-beings in the book. I wondered if that was because the author did not want to risk ridicule in the academic world and/or if she wanted to assert the existence and agency of earth-beings purely through the force of her thinking and investigative rigor, and not refer to any direct experiential knowledge of them.

For Heron and Reason (1997), experiential knowledge is one of the four ways of knowing, alongside propositional, presentational and practical knowing. They define it as:

“Experiential knowing means direct encounter, face-to-face meeting: feeling and imaging the presence of some energy, entity, person, place, process or thing. It is knowing through participative, empathic resonance with a being, so that as knower I feel both attuned with it and distinct from it. It is also the creative shaping of a world through the transaction of imaging it, perceptually and in other ways. Experiential knowing thus articulates reality through felt resonance with the inner being of what is there, and through perceptually enacting (Varela et al, 1993) its forms of appearing.”

For whatever reason, I felt that by denying or omitting her own direct lived experience – even though she was developing a powerful critique of the field of knowledge in which history and science hold sway, and in which some forms of knowledge are legitimised whilst others are ruled out – she was, at the same time, supporting a view of validity that rules out direct personal experience and privileges general abstract, theory. This is the way of knowing called propositional knowing by Heron and Reason.

The next time I read the book, in early March 2017, I paid particular attention to the passages in which the author mentions and describes her relationship with ‘earth-beings’. This gave me a much more nuanced view of her way of thinking and writing about ‘earth-beings’.

To examine these nuances further, in the part of this paper that follows, I want to quote four key passages from the book that I selected which indicate the author’s relationship with earth beings. After quoting the passage, a comparison will be made with my experience with ayahuasca and plant spirits.

a) “I learned to identify radical difference – emerging in front of me through the conversations that made it possible – as that which I “did not get” because it exceeded the depth of my understanding. Take earth-beings, for example: I could acknowledge their being through Mariano and Nazario, but I could not know them the way I know that mountains are rocks.” (p. 63)

She seems to be inferring here that she is not capable at all of knowing earth beings outside the frame of reference of her understanding. This is very different from my knowledge of plant spirits. Possibly the aspect of my experience with ayahuasca when dieting different plants and trees that has most challenged my rational, highly educated mind (that is ‘educated’ in a conventional Western sense) has been my direct experience of encounter with these plant spirits – experiential knowing using Heron and Reason’s typology. At times, this has a noetic quality as described by William James (1902):

“…states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect. They are illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance, all inarticulate though they remain; and as a rule they carry with them a curious sense of authority.”

These experiences of direct encounter with plant spirits have a quality of undisputable and compelling veracity which makes them profoundly meaningful and “more real than reality”. Over time, though, I have also come to see and accept that my experience of plant spirits, which, in my case, generally takes the form of conversations with them, is hugely limited in relation to the experience, knowledge and skill of my Shipibo Maestro.

Through his culture, his family lineage, his early life in the jungle away from Western influences, and for the fifty years he has been working with ayahuasca and dieting other plants, he has a much wider and deeper appreciation of the world of plant spirits. Moreover, he, unlike myself at this stage in my training, can enter into relationship with the world of plant spirits to heal people.

b) “I follow Nazario but only to an extent, because my own relationship with earth beings, albeit mediated by his friendship, is different from his. I do not have the means to access them like he did; I do not know tirakuna [earth-beings], and cannot enact them. Instead I know – and can enact – mountains, rivers, lakes, or lagoons. But I can also acknowledge the complexity of these entities as earth-beings/nature (at once different from each other and the same as each other) that straddle the world of runakuna [human beings] and the world I am familiar with.” (p.167)

Again in this passage, I think the author is acknowledging that her way of knowing earth-beings is limited to propositional knowing and does not include experiential knowing. The phrase ‘mediated by his friendship’, however, is interesting as it indicates that something of the power of Nazario’s knowledge was conveyed to her through his being.

c) “The difference is that rather than extending historicity to include nonhumans in events, following Mariano’s stories, I extend eventfulness to earth-beings – entities whose regimes of reality, and the practices that bring them about, unlike history or science, do not require proof to affirm their actuality. Certainly they cannot persuade us that they exist; nevertheless, our incapacity to be persuaded of their participation in making Mariano’s archive does not authorise the denial of their being.” (p.150)

The intriguing phrase here for me is that “certainly they cannot persuade us that they exist”. That actually runs counter to my experience of plant spirits. I dont think they have any interest in persuading me that they exist but they have revealed themselves to me in a way that has been utterly convincing or persuasive. It could be though that De La Cadena is referring to the idea of persuasiveness within the epistemic regime of science and history, which as she points out, is different from the reality regime of earth beings.

d) “I knew that Nazario was always careful in his relationship with Ausangate and other earth-beings. He never pretended to do what he could not do, and he did not lie. I do not think Ausangate killed Nazario, because I think Ausangate liked him – however, this does not mean I know Ausangate, not even with my head as Benito did. (p.19)

This is one of the most interesting passages in the book. The phrase “because I think Ausangate liked him” is the closest in the whole book that the author gets to personalising her own relationship with the earth-being that is Ausangate. Yet she is quick to add that “this does nor mean I know Ausangate”, although she is clearly expressing a view about the likes and dislikes of this being.

Overall, it is clear that De La Cadena treats the practices of her two collaborators, in which they offer ‘despachos’ or ‘ofrendas’ (best translated as ‘offerings’) to different earth-beings as a way of asking them to participate favorably in human affairs, with great respect. Although she does not say it explicitly, this respect is extended to the earth-beings to whom these offerings are directed. One way of showing this respect is not to talk loosely or reveal too much to an indiscriminate public audience, such as the people reading a book, about one’s knowledge of and relationship with the nonhuman world. This is a feature of esoteric knowledge, which runs counter to the academic tradition, where knowledge has to be made explicit so it can be verified.

Part, therefore, of my more nuanced reading of De La Cadena’s relationship with earth beings is the speculation that she may deliberately be choosing not to talk of her direct experience of them. This might be because her relationship to earth beings, which, like all reciprocally-based relationships, carries obligations, involves the requirement to not speak indiscriminately and carelessly about them. Stephan Beyer (2011) also refers to the obligations assumed in relationship with the plant spirit world and that it is not possible to be a ‘tourist’ or voyeur in this world – genuine reciprocity is demanded. I hypothesize about this possible reticence on the part of De La Cadena to speak directly of her experiences with earth-beings, too, as a result of my own learning, where it was made clear to me that conversations that I had engaged in with plant spirits were not for public consumption on the internet and that doing this curtails the relationship.

iv) Ecologies of Practice: Naming, Uttering and Singing.

To further illustrate the existence of earth spirits, De La Cadena describes the condition of being in-ayllu, which is of utmost significance to the two protagonists of her stories. This concept of being in-ayllu is difficult for the individualist Western mind to fully grasp. It suggests that all beings in a given locality, both human and nonhuman, are related and that, more crucially, it is only through these inter-relationships that individual entities such as persons or earth-beings can arise. As De La Cadena says of the relationships between human and earth beings (p. 207) in writing about the colonial attempt to eradicate what were seen as idolatries:

“It would have also involved transforming the relational mode of the in-allyu world, where earth-beings are not objects of human subjects. Rather, they are together and as such are place. The form of the relationship in-ayllu is different from relations of worship or veneration that require separation between humans and sacred mountains or spirits.”

The part, the individual, is not separate from, or a priori to, but embedded in the whole. Likewise the whole, the ayllu, is enfolded in each part. In the language of chaos theory, each part is a fractal of the whole, and the whole comes into being through its expression in the parts. It does not exist as a transcendent entity.

Cadena quotes a bilingual Quechua-Spanish teacher explaining the term ayllu to her as follows (p. 44):

“Ayllu is like a weaving, and all the beings in this world – people, animals, mountains, plants etc. – are like the threads, we are part of the design. The beings in this world are not alone, just as by itself a thread is not a weaving, and as weavings are with threads, a runa [person] is always in-ayllu with other beings.”

The condition of being in-ayllu carries obligations with it. Throughout the book, it is constantly emphasised that when Mariano, one of the two protagonists, is asked by the ayllu to take on political leadership in the struggle against the hacienda system, this cannot be refused because he is obliged to do so by being in-ayllu, even though doing this entails great personal risk and is met with fierce opposition from his wife.

De La Cadena, furthermore, shows that the practice of relating to earth-beings is difficult for the Western mind to grasp. The most powerful earth-beings are the mountains surrounding the area where the protagonists live and the most powerful of these is Ausangate. The point for Mariano and Nazario is that there is no difference between the name of the mountain and the mountain. In the language of semiotics, there is no separation between signfier and signified. Both the name and the mountain are the earth being. De La Cadena writes: “In this specific case, things (mountains, soil, water and rocks) are not only things; they are earth beings, and their names speak what they are. Ausangate is its name; they do not have names [just] for the sake of it…..I was told.” (p.116):

The earth being is invoked and therefore entered into relationship with by uttering its name. But, as another one of Mariano’s sons points out, this is not just a matter of knowing the right words to say, of reading the right script. The person making the despacho needs a special quality, difficult to describe, but recognised in practice as one who knows.

All this is a very different practice, known in the Western tradition as magic, (and now resurfacing in films and popular literature), where uttering the words invokes the manifestation of those words. A more sophisticated example of this resurgence in interest in magic from literature, apart from the obvious examples of the Harry Potter books and films and the ‘Game of Thrones’ TV Series, is the first of the trilogy of stories called ‘The Name of the Wind’ by Patrick Rothfuss (2007). This details the schooling of a young man who later became a legendary magician, where the most powerful, idiosyncratic, unruly and feared teacher in the school is the one who knows the true names of things. By speaking these names they can be invoked. Again there is no distinction between signifier and signified. For that reason, in many indigenous traditions, words have to be used carefully and eloquently. Prechtel (1999) documents this well when he describes his own immersion into Mayan culture on the shores of lake Atitlan in Guatemala.

James Hillman (1975) makes the same point when he says: “Words too burn and become flesh as we speak”. To quote him further at length, from “Revisioning Psychology” (1975):

“We need to recall the angel aspect of the word, recognizing words as independent carriers of soul between people. We need to recall that we do not just make words up or learn them at school, or ever have them fully under control. Words, like angels, are powers which have invisible power over us. They are personal presences which have whole mythologies: genders, genealogies, (etymologies concerning origins and creations), histories, and vogues; and their own guarding, blaspheming, creating and annihilating effects. For words are persons.”

To bring this discussion into the context of my five years of apprenticeship with my maestro, I experience this non-separation between the words and what they invoke in relation to the healing songs, called icaros, that he sings in ayahuasca ceremonies. He is not singing a pre-prepared song script, as most Westerners typically assume and I used to think. If it is just a song, it can be learned and sung as a song but this is not what my Maestro is doing. (It could be, though, that learning the icaros as songs is a necessary first step to becoming an adept.) What the earth-beings and plant spirits have in common is that they are spoken or sung into being for humans to be able to enter in relationship to them.

My Maestro is singing to what he sees in the visions of his mareación – the name in Spanish for the state attained after drinking ayahuasca. Moreover, it would not be correct to say that it is just him who is singing. The meaning of the words and the grammatical constructions in the icaros take a different form from their use in everyday language. I am deeply indebted to my Shipibo language teacher and linguistic expert, Profesor Eli Sanchez for him pointing this out to me and for his translations of the icaros and interpretations of the way that words are being used differently in them.

One key word that is different is the word for ‘I’. It is not the narrow egoic ‘I’, as it is used in ordinary everyday language, but a much vaster presence that links the ‘I’ of the singer with the authority and knowledge gained through dieting plants. The spirits of the plants that my Maestro has dieted are singing through him. He is a conduit for the plant spirits at the same time that the plant spirits are a channel for him. In the same way as De La Cadena writes about the relationship between her protagonists and their highly skilled practices of entering into relationship with earth-beings, the subject/object distinction collapses.

In the case of my Maestro, the icaro (the song), the plant spirit and himself are reconfigured through drinking ayahuasca in such a way as, De La Cadena would say, following Haraway (1991), that “one is too few but two are two many”. This indicates that my Maestro is not solely one person singing but neither is he multiple persons, as this would imply that this multipicity exists as separate units, whereas all the different forms of being, his human being and the being of the plant spirits, are mutually entangled. For the Western mind, trained in separation and analysis, this is indeed a puzzle.

It is this condition of mutual entanglement, which again, following De La Cadena, following Strathern (2004), we could describe as a series of “partial connections” between the human world of my maestro and the nonhuman world of the plant spirits, that enables him to heal people. It is important to understand the notion of partial connections here not as implying anything to do with the strength of the connection, which in the case of my Maestro is powerful and fully present, but more as De La Cadena writes (p.32) offering “the possibility of conceptualizing entities (or collectives) with relations integrally implied, thus disrupting them as units.”

v) Equivocations.

In this last section of the third part of the paper, I want to address what De La Cadena calls, following Viveiros de Castro (2004b) equivocations. For Viveiros de Castro these necessarily arise from the attempt to understand and translate terms from different lifeworlds.

Since its beginning as a discipline, anthropology has tended to represent the subjects of its study in its own terms, usually racially-laden with assumptions about superiority and inferiority that recreate the power relationships of colonization.

As Comaroff J. & J. say (1991, p. 4): “Whether it be in the name of a “benign,” civilizing imperialism or in a cynical pursuit of their labor power, the final objective of generations of colonizers has been to colonize [the native’s] consciousness with the axioms and aesthetics of an alien culture.”

Vivieros de Castro, in common with a new generation of anthropologists influenced by postcolonial studies, is wrestling with the attempt to understand the cosmovisions of Amerindian peoples, which are so different from those of the anthropologists engaged in studying them, without imposing the terms of their own cultural paradigms upon them, and without eliminating the differences that exist between radically different ways of understanding and engaging with the world.

Viveiros de Castro understands anthropology as translation. His view of translation, and therefore equivocation, is worth quoting at length:

“To translate is to situate oneself in the space of the equivocation and to dwell there. It is not to unmake the equivocation (since this would be to suppose it never existed in the first place) but precisely the opposite is true. To translate is to emphasize or potentialize the equivocation, that is, to open and widen the space imagined not to exist between the conceptual languages in contact, a space that the equivocation precisely concealed. The equivocation is not that which impedes the relation, but that which founds and impels it: a difference in perspective. To translate is to presume that an equivocation always exists; it is to communicate by differences, instead of silencing the Other by presuming a univocality—the essential similarity—between what the Other and We are saying.” (2004b, p. 10):

I want to further explore this notion of equivocation as I have encountered it in my relation with my Shipibo Maestro. To clarify this term: the word Maestro or Maestra is used as a form of respect to acknowledge Shipibo people, who can be called in Spanish either médicos (doctors) or curanderos (healers), that have attained a high level of skill, knowledge and healing ability. In Shipibo, they are called onanya, translated as one who has knowledge. This ability and subsequent recognition is acquired over many years, usually under the supervision of and in apprenticeship with a trusted Maestro or Maestra, often from the same family, (that leads to the creation of family lineages), through the practice of plant dietas.

My Maestro commented, when I interviewed him for a research report I co-wrote (2016) about how Shipibo Maestr@s learn their craft:

“It takes a long time to become a Maestro. It is an education. It is like any young person going to school. First preschool, then elementary, then high school, then university. It is the same for shamanism in order to become a Maestro. But now, there are people who drink ayahuasca for one or two years, then they think they are a ‘Maestro’. They teach: they run dietas. To be a proper Maestro you have to diet for a long time, years and years. That’s what it takes to learn shamanism, in order to be able to learn to heal.”

Plant dietas are essentially a practice that combines the drinking of ayahausca with the imbibing of one or more plants over an extended period – anything from ten days to one year – alongside strong dietary and behavioral restrictions. Through the dieta, the person is able to receive the teachings, healing capacities and icaros (songs) of the spirits of the plants. Ayahausca functions as an interspecies communicator to help bridge the human world and the world of the plant spirits. Traditionally, these dietas were carried out alone, isolated in the jungle, apart from regular visits by the supervising Maestr@.

I first asked my Maestro to become my teacher/Maestro, which implied entering a period of apprenticeship with him, in the fall of 2012. I told him then that I did not imagine myself becoming a healer but I wanted to learn from him in order to do my work better. This work is co-leading a nonprofit called Alianza Arkana, which is a grassroots alliance regenerating the Peruvian Amazon by supporting its indigenous people and their traditions. I was one of the three co-founders of this organization in January 2011 and continue to work with it today as Director of Organizational Development and Research.

My Maestro, in general, is a man of few words. He rarely likes to engage in small-talk although he is always courteous and always asks me about my family, especially my younger son who has worked with him. He rarely engages in explanations, or even dialogue, about what has happened to people in ceremonies and prefers to let his outstanding work as a healer talk for him. He has a powerful, commanding presence in ceremonies yet outside ceremonies is very humble, taciturn and occasionally grumpy. Often, I find him impenetrable.

He was born in 1950 in a small village called Juancito, which is almost the last Shipibo settlement in the lower Ucayali, downriver from Contamana. Hearing him talk about his life growing up there, is to enter a world that sadly no longer exists. There was an abundance of animal life, the rivers and creeks were full of fish, the water was uncontaminated and drinkable, there was very little contact with Westerners, and his family had a deep communion with the forest and extensive knowledge of its medicinal plants.

He was the last of five brothers – all of whom became skilled médicos – and an older sister. His sister, who was the first-born of the six children, and his oldest brother are now dead. His two grandfathers were both merayas, which is the highest level for the Shipibo that can be achieved by a healer. One important indication of being a meraya is the ability to physically disappear.

It is said that there are no longer any living merayas amongst the Shipibo – although some people might like to claim this title. We asked all the interviewees in the research report that I mentioned above why they thought that very few young Shipibo people now want to follow the path to become a médico, let alone a meraya. The main reason we were consistently told in the interviews for the research report is that this path is very difficult. It requires many years of strong discipline and sacrifice. One of the conditions of dietas is that sexual relations (or even touching other people) have to be avoided. The older médicos said simply that young Shipibo people no longer wanted to do this.

My Maestro started his first plant dieta when he was 12 years old. In the interview with him for the previously mentioned research report, he said:

“I first dieted when I was twelve, with my brothers … Also my two nephews. We dieted for a year and a half, eighteen months … This is a very strong dieta … My brothers and I were secluded from people at a distance. Only my mother was allowed to approach us. My father and brothers and I would do ceremonies there … We ate very dried fish, no salt or sugar. We drank tobacco juice. I almost could not stand it. I cried a lot. I was a child! ”

He received no formal schooling and cannot read or write. In his twenties, when he already had a wife and children, he moved upriver to join his birth family who had migrated to live in one of the larger Shipibo communities in the lower Ucayali between Pucallpa and Contamana.

One of the major equivocations I encounter with him concerns what it means for him to be my teacher. Many times, I felt frustrated with the lack of direct guidance and explanations that I received from him. My notion of him being my teacher implied that he would teach me in the way that I was used to after fifty years of Western education. My apprenticeship took the form of doing different plant dietas with him, from between ten and thirty days. In a typical year, I might do this four or five times with him.

One day, around three years after I began working with him, I had a kind of epiphany. He was singing to me in a ceremony and I suddenly realised that he had been doing, and achieving, exactly what I had asked him to. Without telling me in words I could understand, as my Shipibo is still too limited to understand what he was singing to me, he had been working with me to help me more fully take on the leadership of the nonprofit. I could suddenly appreciate that, through his help and the help of the plants that I have dieted, I was now leading the organization in a much more skilled, confident and effective way. I felt somewhat stupid that it had taken me so long to understand this. When I spoke about this later to a friend, she was very helpful in saying to me that his method of teaching was similar to that of a guru she had worked with for many years in India. The method of teaching of her guru was by direct transmission, which we are very unfamilar with in the West.

The following is a description of the method found on a website related to Tibetan Buddhism:

“The uniqueness of the Dzogchen teaching is the direct transmission or “direct introduction” in which the master and the student find themselves in the primordial state at the same moment through one of the experiences related to body, voice or mind. Due to the power of the transmission, the students are able to discover their own real condition in this way.”

This is a good, short description of the teaching method of my Maestro, though I doubt he would ever formulate it in anything like this way.

Two more examples of equivocations come to mind. One occurred at the end of a ceremony, in my Maestro’s village, which had been marked throughout by loud music and drunken shouting from a recently opened, nearby bar. I had been thinking about how the young people in the community were gravitating towards alcohol, reggaeton music, gasoline-fuelled generation of power, and other pernicious (in my view) Western influences. I began to talk to my Maestro about this and asked him how old the people were who had been at the bar. He did not seem to understand my question. When I repeated it, he answered in terms of the names of the young people whom he thought had been present at the bar and who, in the community, they were the sons of.

I did not think this reply was because he had misunderstood my Spanish. He heard me asking about these young people and instead of answering in quantitative terms about their age, he answered me in terms of their relationships to the community. We had different notions of identity: mine was in terms of age and his was in terms of relationship.

The second example is more recent when I was dieting with him and a group of people for thirty days in Yarina, the mainly indigenous part of Pucallpa. One of the people doing the dieta was seriously ill with prostrate and bone cancer. Towards the end of the dieta, the Canadian woman organizing the dieta asked me to translate a question from English to Spanish to my Maestro asking him what the ill person could do after he returned to his country to help him continue to get better. Again, it seemed to me that my Maestro did not understand the question, although his Spanish is good. I repeated it a number of times but did not really get a response. Afterwards, I thought that he did not understand why I was asking the question. From his point of view, he had said everything that needed to be done for the continuing treatment. I thought, afterwards, that asking him about this was potentially an insult for him and questioning his work – if he had had any more to say about how to treat the illness, he would already have said it.

Understanding better the inevitability of equivocation and that it is not a mistake or misunderstanding, but rather a means by which otherness can be seen, helps give me a window into the perplexities, confusion, frustration, joy and satisfaction of my relationship with my Maestro. I can see that I also must perplex him. He calls me ‘Doctor’, due to my academic title, whereas to me he is the médico. I call him ‘Papa’ all the time and he very occasionally calls me ‘hijo’ (son). As Vivieros de Castro points out (2004b) his equivocations will be different from mine. In a Western world, I would try and talk to him about our relationship, how we misunderstand one another, what strategies we might use to better understand one another but I think he would have no idea what I was talking about nor would it interest him.

Ending Comments

At first I struggled with the end of this paper. How could I summarize and wrap everything up neatly, as I thought a good conclusion demanded.

Then I realized that my difficulty in doing this was because, given the nature of what I have been writing about, there is no tidy conclusion. Its nature is open-ended, unfinished, full of partial connections, equivocal rather than univocal, and necessarily resistant to an overall totalizing discourse.

To paraphrase Magritte, this is not a conclusion.

Thank you for reading this far.

References

Beyer, Stephan V. (2011) What do the Spirits Want from Us? The Journal of Shamanic Practice. Vol. 4 Issue 2 pp.12-16

Comaroff J. & Comaroff J. L. (1991) Of Revelation and Revolution: Volume 1, Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa. Chicago: Chicago University Press

Descola, P. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture, translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De La Cadena, Marisol. (2015) Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds’. Duke University Press

Haraway, Donna J. (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge

Heron, John and Peter Reason (1997) ‘A Participative Inquiry Paradigm’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 3 No. 3.

Hillman, James. (1975) Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: Harper & Row

James, William. (1902) The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. Longmans Green & Co.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Latour, Bruno, (1993) We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lawrence, D.H. (2014) Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays (The Cambridge Edition of the Works of D.H. Lawrence) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prechtel, Martin. (1999) Secrets of the Talking Jaguar: Memoirs from the Living Heart of a Mayan Village. TarcherPerigree.

Roberts, Paul and Laura Dev (2016) Research Report: Learning from the Peruvian Amazon. Accessed on 23rd March 2017 at: http://www.roffeypark.com/research-insights/free-research-and-insight-report-downloads/

Rothfuss, Patrick. (2007) The Name of the Wind. New York: Daw Books Inc.

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. (1985) Leviathan and the Air Pump: Hobbes, Boyle and the Experimental Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Strathern, Marilyn. (2004) Partial Connections. New York: Altamira

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. (1998) “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivalism.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4, no. 3: 469–88.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. (2004a). “Exchanging Perspectives: The Transformation of Objects into Subjects in Amerindian Ontologies.” Common Knowledge 10 (3): 463-484

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. (2004b). “Perspectival Anthropology and the method of Controlled Equivocation.” Tipití 2 (1): 3-22

This is the second part of a paper that I presented at the recent Latin American Studies Association (LASA) conference in Lima.

The first part of the paper, called called ‘Introduction: Origins, Globalization and Uses of Ayahuasca’ can be read here.

The second part of the paper, reproduced below, looks at the typical sense-making discourses Western people use to understand their ayahuasca experiences and argues that they are all located in an overall paradigm that reproduces the dualistic splits between subject and object and nature and culture, which have been a feature of mainstream Western thought for the last four hundred years, that, ironically, the ayahuasca experience profoundly challenges. This part of the paper ends with looking at three thinkers – Jung, Hillman and Corbin – whose work, by giving primacy to the imagination, offers a different perspective on the experience of drinking ayahuasca.

Finally, I have created the time to write the blog post I have been intending to write for a while.

I have been very busy in the last few months with the work of the nonprofit, Alianza Arkana, I help lead here in Pucallpa, in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon.

As always, the work has been challenging, complex, intense, absorbing and satisfying.

This blog post grew out of the proddings of a good friend who has been regularly sending me material related to what can be called the Christian Wisdom tradition, as exemplified in the work of Teilhard de Chardin and Dr Cynthia Bourgeault. A few weeks ago, I watched the video on YouTube with Cynthia Bourgeault being interviewed by Renate McNay, on the Conscious TV channel.

I can’t recommend this video highly enough. You need 55 minutes of quiet time to watch and absorb it, and another ten minutes to do the suggested meditation at the end.

image found at: http://theconversation.com/ayahuasca-the-shamanic-brew-that-produces-out-of-body-experiences-52836

As the use of ayahuasca expands across the globe, so the number of articles about it grows. It’s interesting to see, too, the proliferation and variety of discourses used to decribe the medicine – new age, scientific (notably neuroscientific), psychological, healing, ecological and political.

The following are the best and/or most interesting articles on ayahuasca that I have seen in the last few months. Read more…

Recently, following the recommendation of a friend, I watched the movie, ‘The Sound of my Voice’. The low budget (only $135,000) movie was a hit at the Sundance Independent Film Festival in 2011.

The movie is the story of two wanna-be investigative reporters, a couple in their twenties, who infiltrate a cult in los Angeles, with a view to exposing the leader – an attractive, blond women, dressed in flowing white robes, memorably described in one review of the movie as looking like “the Pilates instructor on the Starship Enterprise”. She claims to be from the future, specifically the year 2054. She says she has returned to the present to warn people of the impending civil war and disasters that are due to happen, and prepare people for this.

As the movie unfolds, we start to see the tensions between and the complexities of the motivations of the two people investigating the cult. Furthermore, as they become more involved with the cult, their role as detached investigators, looking for the truth in order to expose it, becomes more problematic. Read more…

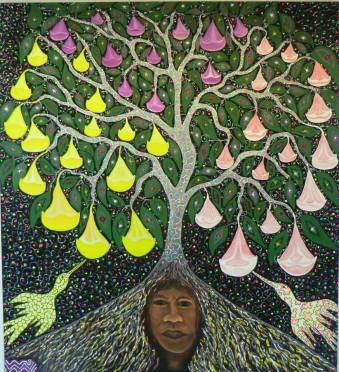

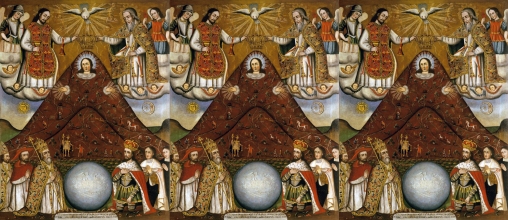

Anonymous, Virgen-Cerro, c. 1730. Museo de la Casa Nacional de Moneda, Potosí. The painting represents an Earth-being that is also a mountain, occupied by the Virgin and guarded by the Church, from where the Devil might have been expelled. Found at: http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/authors/marisol-de-la-cadena/

This blog entry continues a sequence of writing about books I have read whilst in dieta. Recent posts have included commentaries on Henri Corbin’s book ‘Alone with the Alone’ about visionary experience and Thomas Moore’s book ‘The Planets Within’ about the Renaissance astrologer and psychologist of the soul, Marcilio Ficino.

As I have commented before, reading books whilst doing a plant dieta, is different from normal reading. Because of the intense receptive state a dieta creates, which is why it is important to monitor one’s contact with different energies – traditionally for the Shipibo dietas were done in isolation in the jungle – one absorbs the energy of a book. Ideas, as James Hillman pointed out, are living entities and they have their effects on our psyches. Read more…

For a number of weeks now, I have felt burdened by the responsibilities I have assumed in the collective leadership of Alianza Arkana – the nonprofit I work with here in the Peruvian Amazon. I can see there are practical reasons why I might feel burdened – a number of talented and committed long-term volunteers have recently left, who shared the responsibilities of leading a non-hierarchical organization. Read more…

Portrait of Ibn ‘Arabi found at: http://www.amaana.org/ismaili/ibn-arabi-diana-steigerwald/

Whilst on my recent 14 day dieta with Don Ayahuma, I read the second 100 pages of Henri Corbin‘s book ‘Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi’. I previously wrote about the first 100 pages of this book here. In this earlier blog, I wanted to show that Corbin has much to offer in providing a detailed phenemonology of the visionary realm.

If Thomas Moore’s book ‘The Planets Within’, which was the other book I read on the dieta, (and which I wrote about in my last blog post), is subtle and complex, Corbin’s book is even more demanding on the reader. This is because Corbin is exploring, with great erudition, traditions within mystical Islam that have had relatively or little no impact within mainstream Western thought and are therefore unfamiliar to us. Read more…

About one month ago, I returned from a 14 day ayahuma dieta with my Shipibo Maestro. A strict contract of confidentiality with Don Ayahuma prevents me saying much about this dieta. Suffice it to say, that my impressions were re-confirmed that this is a powerful shamanic tree and should not be treated lightly or disrespectfully (as indeed nor should any plant/tree dieta) – which means focussing on and observing the conditions of the dieta.

Whilst on this dieta, I read Thomas Moore’s book ‘The Planets Within’. As I have commented before, you have to be careful what you read when doing dietas, as you diet the book as well, especially given that there is little other external stimulation coming into your mind – bland food, no TV, no computer, no phone, ideally, very limited social contact. So, reading any book in these conditions of heightened sensitivity and openness, makes a big impression. Read more…